The Reasons For Standard Guitar Fretboard Tuning

How To Deal With That Unexpected Major Third And Other Things

In this article, we're going to figure out why the current guitar standard tuning is E A D G B and E. We'll also learn a mental model useful to deal with the irregularities of the layout.

We will take a journey back through the years to understand how ancient stringed instruments influenced the shaping of our beloved axes as we know them today.

Guitar Standard Tuning

From a logical point of view, the standard tuning seems easy to understand. Each string is a Perfect Fourth apart (5 half-steps, or 5 frets).

- From the low E string to the A string, we have 5 frets.

- From the A string to the D string, we still have 5 frets.

- The same from the D string to the G string.

- From G and B, we'll see in the following...

- Also between the B string and the high E string there is a Perfect fourth.

Things change between the G string and the B string. In fact, they are 4 half-steps apart, a Major third instead of a Perfect fourth.

Why is that? What if the guitar tuning would be in all fourths, in order to have a perfect grid composed of E, A, D, G, C and F strings?

With this setup, we could easily shift the same pattern across the fretboard, vertically and horizontally, without thinking too much!

Well, the all fourths tuning actually already exists, musicians like Stanley Jordan appreciate it because "it simplifies the fingerboard, making it logical".

But we are here to discover the reasons that gave birth to the standard tuning, so let's find out them!

A Brief History of Stringed Instruments

Stringed can instruments have different tunings.

The violin, the cello and the mandolin, are tuned in fifth intervals.

The lute in thirds, while the guitar and the double bass in fourth.

The tuning depends on the size of the instruments, and the type of music part that the instrument have to play (chords, lead, backing lines).

The guitar inherits its tuning system from renaissance plucked stringed instruments, that through the 1600 to 1750 period replaced the lute.

Initially, those Renaissance guitar had four strings, tuned like the first four string of guitar, so a fourth (E to B), a third (B to G), and a fourth (G to D).

Then, through the years, two more strings added, the A, and the E low string, so we got our familiar 6 strings standard tuning.

The standard tuning is a good compromise between comfort and easiness for playing chords and melodic lines, having bass on open strings, especially for the type of music composed in the 8th century.

Why Does The Highest String Note Is E?

Have you ever wondered why the 1st string of the guitar is tuned to E, and not to F, C, B, or another note?

In ancient times the tuning of stringed instruments was not fixed, but the usual advice was to pull the first string until the sound was satisfying.

Then the musician could tune the other strings accordingly, using the 1st string as a reference.

At that time strings were made of gut, so they could not be stretched too much.

As the critical factor was the first string, which was the thinnest and given the length of the neck on a guitar, the best intonation note that did not break it and was pleasing turned out to be the note E.

How To Adapt Guitar Shapes Across The G and B Strings

Ok, enough talking about the past and ancient instruments.

Now we're going to see some practical advice that will make crossing the G and B strings easier.

We've just seen that all the strings of the guitar are a perfect fourth apart (5 frets) except for the G and B strings which are a major third apart (4 frets), one fret less than the other strings.

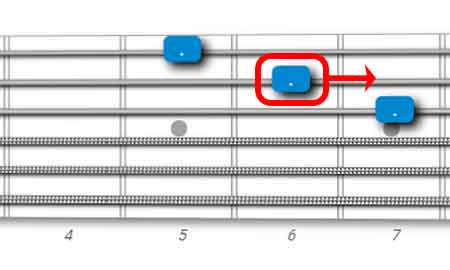

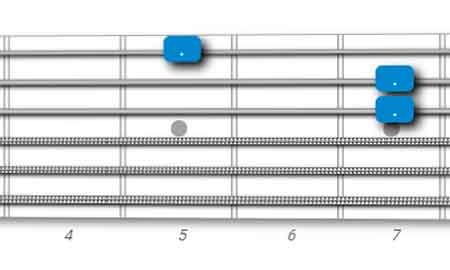

Due to the inconsistency between the G and B strings, any fretboard pattern that crosses those two strings must be shifted up by one fret, in order to compensate the smaller interval between G and B.

The images below should help you understand this concept better:

Example: Shifting Vertically A Major Scale

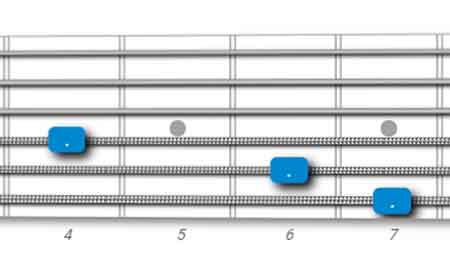

This is a simple 4-fret-box scale pattern for the major scale, with root on the 8th fret of the 6th string. So it's a C major scale.

We have just moved the whole group to the upper strings. Now the root is F, the note located at fret 8 of the A string.

As we did not crossed the B string, the shape is remains the same.

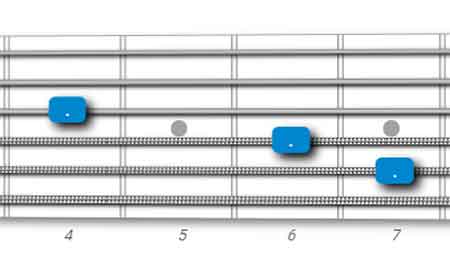

We go up one more string, now the root is on the 8th fret of the D string, which is a A#. The 3 notes that lies on the B string, must be shifted one fret up to compensate the major third distance between G and B strings.

Ok, now we have the A# major scale pattern adapted for the D, G and B strings.

Try it by yourself on your guitar.

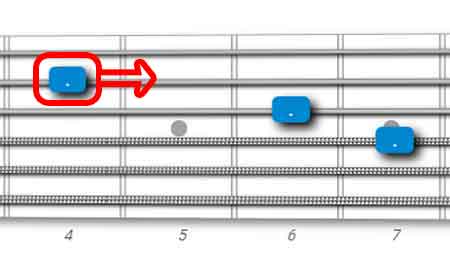

If we move the previous shape on one string higher, we must shift up again the notes that land on the B string.

Note that we move exclusively the notes on the B string, the other elements of the shape remain untouched.

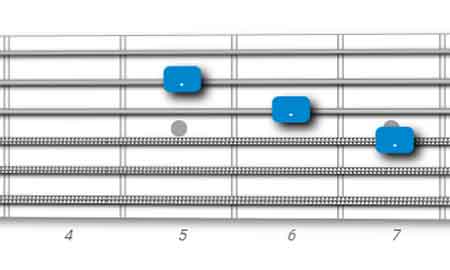

Here you can see the final adjusted shape, a D# major scale with root on the G string.

Example: Shifting Vertically A Major Triad

Now we repeat the same process for a major triad, in this cass a B major triad with root on the E low string.

If we move the whole shape from the E low string to the A string, we don't have to change anything, as the shape did not involve the B string.

If we move the shape one fret higher, we have to shift up by one fret the note that lies on the B string.

And we get a major triad with root on the G string. This is a A major triad.

Again, moving one string up further, we need to shift up the next note that lands on the B string.

Finally, here is our major triad shape with root on the G string. In this case, we have a D major triad.

Guitar Fretboard Tuning: Conclusion

Being fully aware of that inconsistency between G and B strings, allows you to apply guitar shapes on the entire fretboard instinctively.

When you find yourself crossing the G and B strings, get used to doing the mental trick we have just seen to adapt any shape on the fly.

A great exercise is to play ascending intervals on a pair of strings, starting from the E low string up to the higher strings.

That's all, to stay updated, subscribe here.