How To "Make It Stick" for Guitar Players

Effective, Science-Based Music Memorization Strategies

If you've been studying guitar and music theory for enough time, you already know that the memorization of concepts plays a big role.

Being able to recall instantly the formula of a scale, the fingering for a chord, or simply the name of notes on the neck is a skill that lies at the foundation of more complex activities, such as improvisation and songwriting.

In this article, I want to give you some insights into how our brain learns and memorizes things.

Sadly, many players study guitar through endless repetition of the same movements, and by rereading of books and blocknotes: this is not the most effective strategy. You'll learn better approaches in the following of this page.

All the strategies listed on this page are science-based and supported by rigorous experimentation, you'll find some references at the end of the tutorial.

Table Of Contents

Three Types of Memory

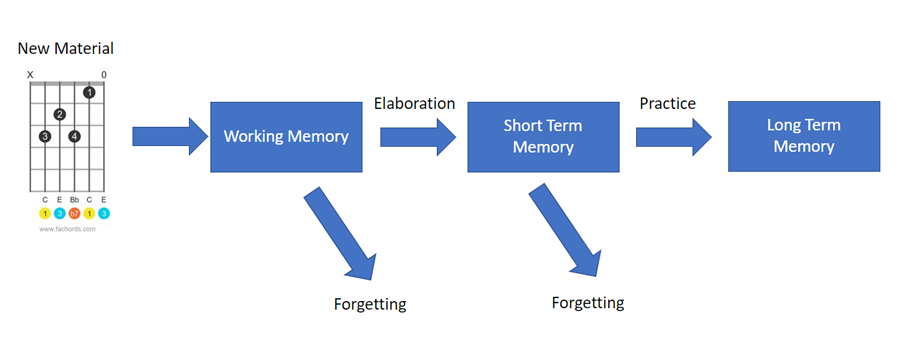

It's helpful to use a framework in which classify the three types of memory we use: working memory, short-term memory and long-term memory.

It's a simplified model that neuroscientists out there will not like too much but it serves its purpose.

Working Memory

The working memory is where we put things we are dealing with in the current moment: for example, a guitar tab we want to learn, or a chord shape we want to master.

It has a limited capacity, usually, it can manage about 7 items (technically called chunks): 7 digits, 7 words, 7 notes, 7 frets, and so forth.

The working memory is the interface between the perceived external world and the processes of reasoning, planning, problem solving and, obviously, learning.

Short Term Memory

Short-term memory contains very recent memories, like the exercises you practiced yesterday, or the breakfast you had this morning.

Information in short-term memory is temporary unless you put effort into storing it in the long-term memory (we'll see how in a moment).

Long Term Memory

Long-term memory goes back months and even years, and preserve things like the C major shape you learned ages ago or your graduation day.

Its capacity is potentially infinite, and once encoded, information lasts a lifetime.

Basically, our final practice target is to push things from working memory to long-term memory, in order to have the concepts embedded in our brain and ready to use, wheter it's a matter of motor skills or a theory concept.

That's easier said than done, right? Don't worry, we are going to unveil some useful strategies.

Why Massive Repetitions Are Not The Most Effective Strategy

They say "practice, practice, practice".

So we tend to perform endless repetitions, in order to master a piece of knowledge. Suppose we want to learn a scale pattern: the standard approach is to play it up and down for hours until we have nailed it down.

Or we want to memorize the chords in the G major key: we read and reread our chords table hoping to memorize it soon.

Massive repetitions are not effective because they bring rapid gains, but also rapid forgetting (which we don't notice), as we are staying in the realm of working and short-term memory.

This is the so-called "Illusion of Mastery": the familiarity with the material due to the repetitions gives the illusions of a fruitful learning session, but the brain is bad at evaluating itself; often it mistakes easiness with effectiveness.

Retrieval Practice For Better Retention

A more effective learning strategy is retrieval practice.

Active retrieval is more effortful, but brings stronger benefits: the memory retention of the material is way better compared to simply repetitions.

Think quizzes or flash-cards vs re-reading notes.

Science demonstrated that effort equals retention; the harder the recalling, the better the learning.

So, an important part of your practice session should be focused on active retrieval: you can create your own flashcards to test yourself on music theory concepts, use my fretboard trainer and music theory quiz, or other creative strategies (have you ever considered using 6 sided dices for generating random chord progression to test yourself?)

Retrieval practice helps you move concepts from working memory to long-term memory because the act of recalling put into action deep mechanisms in our neural system and create new structures that can potentially last forever.

Practice Repetitions The Right Way

Of course, repetitions are still extremely important to advance your skills; there are though specific kinds of repetitions to use: spaced, interleaved, and varied repetitions.

Spaced Practice

The brain elaborates new material in the background, even while you sleep or do your chores. It needs time to consolidate memory, so spanning your repetitions over time is a smart move: enter spaced repetitions.

It's far better to practice and do recalling 5 times distributed in a day, than 50 times once a week in a single session.

Once you start getting familiar with the new material, you can apply a more elaborated spacing strategy, to help the brain store information in the long term memory:

- Practice the material every day

- Practice the material once a week

- Practice the material once a month

- Bingo! You've burned the new material into long-term memory

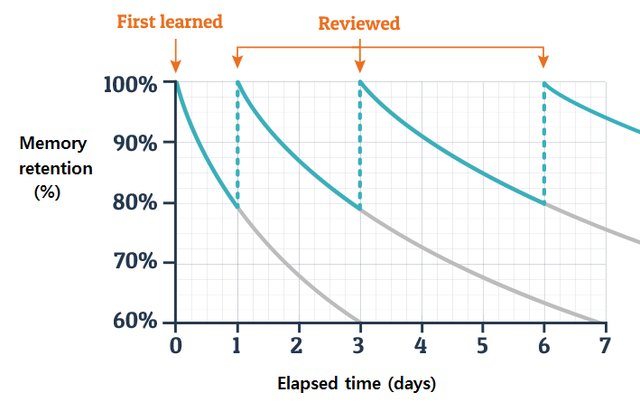

Spaced repetitions goes along with the forgetting curve, a model that describes how information learned fades away if we don't practice recalling it.

Source: Researchgate.com

It perfectly matches with spaced repetitions, because, if spaced correctly, repetitions contrast the forgetting effect in the most effective moment.

There is a cool software out there, Anki, that helps you create your own flashcards and implement spaced repetitions with them.

Interleaved Practice

Here's another big tip: instead of practicing one single concept, practice two or more in the same session.

Want to study the Lydian scale? Good, but practice it along with the Major Scale and the Mixolydian scale. In this way, you will help the brain spot similarities and differences (the #4 of the Lydian mode, and the b7 of the Mixolydian mode).

Want to practice ear training? Practice 3 or 4 interval kinds in the same session, not just one.

Learning is more effective when you put new knowledge in a larger context.

Varied Practice

We can further help our brains and optimize sessions by introducing subtle variations.

Research has shown that little differences in exercises help the learning process.

For example, while practicing a scale pattern, we can use different rhythmic subdivisions, accents, or playing the shape starting from different frets: the spacing between frets changes moving up or down the neck; this variety is helpful for encoding new left-hand movements.

Conclusions and References

I hope that this article gave you new ideas and insights for designing your science-based practice session.

Being aware of how our internal systems work is a great advantage that we can use for practicing better.

Often we don't have time for carrying out our passions, but using a smart approach we can exploit time in the most effective way and reach our targets more easily.

I leave you with some references and don't forget to subscribe here to stay updated on new content.

References

- Peter C. Brown, Henry L. Roediger III, Mark A. McDaniel Make it stick: the science of successful learning, Belknap Press 2014

- Benedict Carey, Forget what you know about good study habits, New York Times 2010

- Doug Rohrer, Kelli Taylor The shuffling of mathematics problems improves learning, Springer 2007

- Nelson Cowan What are the differences between long-term, short-term, and working memory?, Prog Brain Res. 2008